I was genuinely happy abroad — in hindsight, it feels surreal. Was life really that easy? The vibrant nightlife, spontaneous weekend plans, the comfort of global affordability — the list is long. Work rarely dominated conversations with friends or..coworkers. Life felt spacious, lighter. My nerves weren’t constantly frayed. I was certain I’d never move back to India.

Occasionally, during my annual visits home, I’d find myself romanticising life in India. I’d wonder at the comfort of slipping back into my mother tongue, blending in with the crowd, the quiet assurance that comes from growing up in a place and knowing how it works — how to navigate unspoken rules. The ease of meeting friends without syncing calendars a month in advance. The food, too — cheap, abundant, and deeply satisfying. From afar, I was deluded to think of India as a place I could see myself returning to. I also forgot count in the fact that my savings rate working abroad was so good that money did not feel like an issue anymore!

Now I get it — how foreign tourists make dumb comments with their curated version of India. When your life is comfortable and nervous system is well-regulated — when life is orderly and kind — even chaos looks charming. I see now that my longing was filtered through a similar lens. And that understanding has arrived, slowly and painfully, only after returning for good. The common comments privileged visitors to make in India usually follow the below pattern.

“India is so spiritual—everyone just seems so enlightened.”

Yes, nothing says enlightenment like Twitter fights over religion and a two-hour commute through smog. People here are trying to live, not levitate.

“I love how chaotic everything is—it’s like organized chaos!”

Cute when you’re in your hotel taxi with nowhere to be. Less cute when you’re stuck everyday behind a cow, two rowdy Thar and three potholes on your way to job everyday.

“The colours are so vibrant—everything is just alive!”

Grimy pollution, infrastructural decay, and encroached footpaths are certainly a great way to be alive.

“The food is just so pure and organic here!”

I’m glad your 1000-bucks smoothie in Goa was “healing.” Try setting up a house without expensive water purifiers and double-boiling it to save yourself from Typhoid.

However cringe the above comments are, the point I am trying to make here is that living abroad for too long makes you forget how unlivable India really is. But actually moving back to India after living abroad is like having X-ray vision. You suddenly see all the cracks and all at once. And by then…it is all too late.

India is a daily assault on your senses

You are mentally traumatised within the first couple of hours of waking up. It doesn’t surprise me anymore why everyone here is so grumpy and unhappy. Let me illustrate, from the moment you wake up – the first noises you hear are not of nature or birds. You are greeted by the long honking of trucks on the road and traffic that is starting to build up. If that doesn’t affect you, then prepare for all the multiple doorbell rings right from the garbage collector to the dhobi. Its like everyone is just trying to get themselves into your house in the morning like a coordinated SWAT team. Forget your relaxing cup of coffee. It does not happen.

And somehow, you manage to leave for work on time — bracing yourself for the chaos outside. It feels like stepping onto a battlefield, surrounded by warriors in a hurry, each one fighting their own imagined war. Your 9 AM meeting means nothing for the Bhaiya on rickshaw casually parked in the narrow road and talking to his friend. Watch as government buses barrel through traffic, as if shielded from consequence, unstoppable and unbothered. Their brake lights don’t work and bus stops are only for beggars to sleep. The buses will stop right in the middle of traffic, and dare you say anything to them. Around them, chaos swirls. Horns blare in a kind of desperate chorus, while people weave through the madness, fighting for inches of space like soldiers in an urban battlefield.

Some days, you’ll see bikers sprawled on the pothole-ridden roads after a crash. Other days, a truck lies belly-up, its cargo spilled, creating serpentine traffic jams that stretch for kilometres — like a slow, suffocating creature wrapping around the city. Cars come to a standstill over the smallest scuffle, as two drivers lock horns in a ritual of ego and pent-up frustration, turning the road into their personal arena.

This daily assault on your senses — the blaring horns, the chaos, the sheer volume of everything — can wear down even the most patient mind. Add to this the pollution and fumes from ageing vehicles mixed with the sweltering summer heat. It’s a jarring contrast to the mornings I once took for granted abroad. Its inhuman and Indians go through this daily with no hope of improvement in sight.

Civic sense is much worse than what you’d expect

There’s a viral video doing the rounds — an Indian woman eating Dal-Chawal on the London Tube. Beyond the secondhand embarrassment it sparks globally, it reflects something deeper and more troubling within the diaspora: a mindset shaped by scarcity and a kind of short-sighted pragmatism. In his book Games Indians Play, V. Raghunathan explores how, in environments where resources are limited, individuals often prioritize immediate personal gain over collective well-being. This behavior, while understandable in a context of competition for scarce resources, can lead to actions that disregard broader social norms and long-term consequences in any society.

One of the most abysmal examples I can think of is Golf Course Road in Gurugram (formerly Gurgaon). It’s arguably one of the most premium stretches of real estate in the country — a wide, immaculately paved road lined with luxury towers, corporate campuses, and some of the most expensive residential projects in India, like The Camellias by DLF. It’s the kind of place where Bollywood films are shot to give the illusion of a glossy, utopian India.

And yet, the walls lining this very road are smeared with paan stains – the entire stretch with not an inch spared across the kilometres. Bright red blotches, unapologetically splattered, like wounds on a body that was built to impress. It’s disgusting — but also sadly typical.

This road, maintained privately by DLF, is the kind of infrastructure that could never survive under the purview of a municipal body. And perhaps that’s the tragedy: you can build world-class infrastructure, pour in private capital, pave every inch with glass and concrete, but eventually, someone will still spit on it, urinate on it, or dump their trash there.

It’s not just poor civic sense. It’s a deeper cultural disconnect — a mindset that doesn’t see shared spaces as worthy of care. A refusal to believe that public cleanliness is a shared responsibility, not a luxury service. Yet these same people tend to take offense on Twitter when foreign travellers expose the abysmal hygiene and cleanliness of the country

Feeling unsafe and hapless is the norm

Believe it or not, within just six months of moving back to India, I found myself being grabbed by the collar by an autorickshaw driver. We had agreed on a fare of ₹150, but when we reached the destination, he suddenly demanded ₹200. When I stood my ground, he got aggressive — and in that moment, I realized how powerless you can feel.

There was no authority to turn to. No one around intervened. And I knew better than to expect the police to show up — let alone take my side in a petty fare dispute. That’s when it hit me: this isn’t just about one bad encounter. It’s about the deeper truth that here, you’re often left to fend for yourself.

In a system that lacks accountability at every level — from traffic disputes to full-blown crime — people learn to take matters into their own hands. And when you do engage with antisocial behavior, you’re not protected by structure or law. You’re just hoping that it doesn’t get worse.

Bollywood sells us stories of poetic justice and karmic payback. But in real life, justice rarely arrives — and certainly not on time. What you’re left with is a quiet, exhausting calculation: is it worth standing up for what’s right, when the system around you doesn’t stand with you?

In the countries I worked in before, seeing a police officer evoked a sense of safety — even comfort. You’d almost want to smile or nod out of respect, knowing they were there to help, not harass.

In India, this script flips entirely. My first instinct isn’t relief — it’s fear.

Driving in Delhi means constantly navigating aggression, not just from the Thar boys driving like they own the road, but from traffic cops too. And it doesn’t matter if your paperwork is flawless. If you get pulled over, prepare to handover a ₹1000 bribe just to get out of the stoppage.

Here, law enforcement doesn’t work. Personal safety is non-existent and need I even get into the topic of women’s safety in India?

Work life balance is still a joke

Hobbies, what’s that?

When I moved back to India, I expected a poor office culture. We all know Indian offices are notorious for their politics. It all emanates from the scarcity mindset. I was just unprepared at how bad the work culture would feel. In my years abroad, having a police car drive past made me feel safe. Similarly, logging off at 5:30 PM wasn’t just accepted — it was natural. People had hobbies, lives and dinner plans. In India, though, work doesn’t end. It follows you like the Delhi smog: invisible, inescapable, and always a few breaths away from choking you.

Within weeks of resettling, I learnt of coworkers who casually admitted he hadn’t taken a proper vacation in four years — “Not worth it,” he said. “You just return to 600 emails.” Another NRI I knew who had returned from the US was in disbelief. “Back there, I worked 10 hours and had time for myself. Here, 10 hours is just the starting point. You’re either burnt out, or you’re made to feel guilty for not being burnt out enough.”

Statistics back up what every bone in your body starts to feel once you start working in India. The International Labour Organization ranks India among the worst globally for work–life balance. Over half the workforce clocks more than 49 hours a week — many without overtime pay, benefits, or even the illusion of rest. A recent report by MediBuddy shows that 62% of Indian employees suffer from burnout — triple the global average.

But it’s not just the hours; it’s the mindset. Overworking is worn like a badge of honour, a measure of loyalty, of self-sacrifice. Rest is indulgent. Hobbies are frivolous. Art, music, reading, or even just doing nothing is quietly judged — or dismissed outright — as a waste of time. In all my time abroad, I met engineers who brewed craft beer, lawyers who danced salsa, software developers who painted. Here, nobody discusses hobbies because no one has any — weekends are for catching up on sleep and work left from the past week or preparing for the upcoming one. You ask someone what they do for fun, and they look confused, then reach for Netflix.

Even the infrastructure doesn’t cooperate. Commutes in cities like Delhi, Bengaluru, and Mumbai stretch into hours. By the time you get home, drained from work and road rage, you’re lucky if you have the energy to eat, let alone explore a passion project.

The worst part? The system doesn’t just allow it — it glorifies it. Case in point: SN Subrahmanyan, the chair of Larsen & Toubro, shared his point of view when he suggested a 90‑hour workweek and announced, “I regret I am not able to make you work on Sundays… If I can make you work on Sundays, I will be more happy because I work on Sundays too. What do you do sitting at home? How long can you stare at your wife?”

So when people ask what surprised me most about moving back, in addition to the noise, the traffic and the bureaucracy. It’s how willingly we’ve accepted a lifestyle that leaves so little room for being human. No one is happy, everyone is just breathing bad air, working like a donkey and preparing to die unfulfilling lives.

Your CTC Doesn’t Reflect What You Can Actually Afford

This was probably one thing that would have definitely helped me when I was packing my bags to India. I might as well have downgraded my role abroad than move to India at a so-called CTC package. CTC packages in India are only nice on the surface. Indian companies have mastered the art of crafting CTCs that look great on paper. CTC in India is marketing spin – an illusion. Your CTC could be high, but your in-hand salary is what defines your purchasing power.

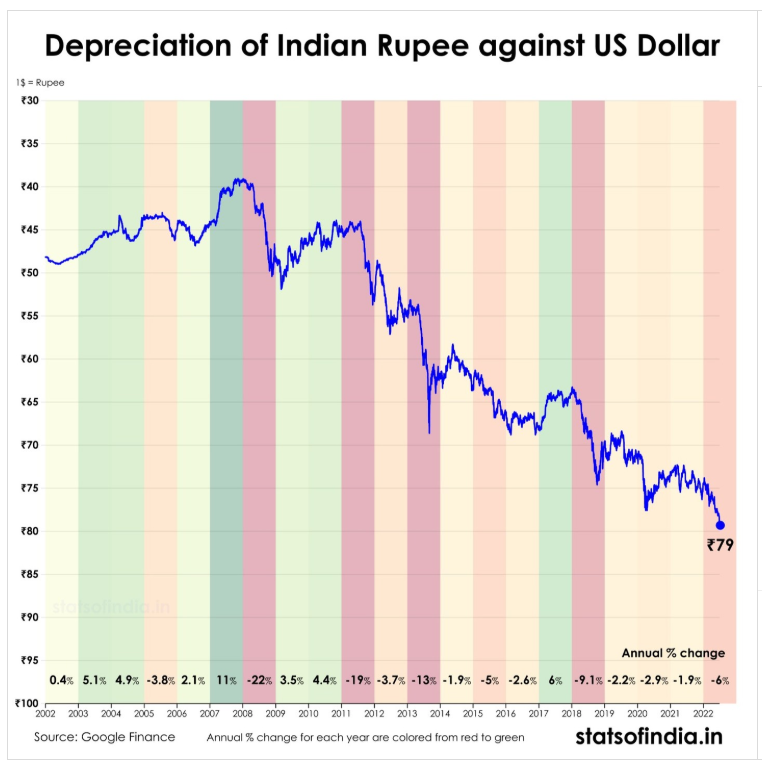

Let me be blunt — India is expensive. Shockingly so. For a so-called “developing country,” daily living costs match or exceed those in major global cities, while the average corporate salary remains, well… very Indian. A domestic flight from Delhi to Bengaluru can cost ₹10,000 — now imagine doing that for a family of three. One dinner at a moderately nice restaurant? ₹1,500 to ₹2,000. That’s on par with what I paid in cities like Shanghai and even Berlin. Beer from a store can cost ₹300 a bottle — at a restaurant, it’s up to ₹800. Fuel hovers above ₹100 a liter. Every small convenience quietly drains your wallet. This is why an NRI working in the US will always get wealthier, because they are able to save a much larger percentage of their income. Indian income is hard to save.

And if you’re thinking of that dream international vacation — brace yourself. The rupee is constantly losing value, and foreign travel is increasingly a luxury even for the so-called “upper middle class.”

The harshest part about taxes in India? One job loss or medical emergency can wipe you out. Indian taxes you mercilessly, yet what you get in return — public healthcare, infrastructure, social protections — is zero.

What it means to move back to India…

In the end, you are stuck at a place where you can’t unsee the cracks but neither can you fix them. I do not know if there is a point where I will feel OK about my decision to move back to India. Its been a couple of years and each morning I wake up with a heavy heart of regret. Maybe that day will come where I forget my past life abroad and the joy and finally find myself living each day in India.